Aladdin (1992 Disney film)

| Aladdin | |

|---|---|

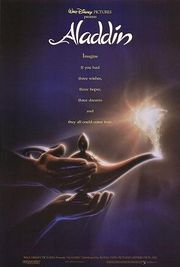

Original theatrical poster; art by John Alvin |

|

| Directed by | Ron Clements John Musker |

| Produced by | Ron Clements John Musker |

| Written by | Ron Clements John Musker Ted Elliott Terry Rossio |

| Starring | Scott Weinger Jonathan Freeman Robin Williams Linda Larkin Frank Welker Gilbert Gottfried Douglas Seale |

| Music by | Alan Menken Howard Ashman Tim Rice |

| Editing by | Mark A. Hester H. Lee Peterson |

| Studio | Walt Disney Feature Animation |

| Distributed by | Walt Disney Pictures Buena Vista Pictures |

| Release date(s) | November 25, 1992 |

| Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $28 million |

| Gross revenue | $504,050,219 |

| Followed by | The Return of Jafar |

Aladdin is a 1992 American animated adventure film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation and released by Walt Disney Pictures. Aladdin was the 31st animated feature in the Walt Disney Animated Classics series, and was part of the Disney film era known as the Disney Renaissance. The film was directed by John Musker and Ron Clements, and is based on the Arab folktale of Aladdin and the magic lamp from One Thousand and One Nights. The voice cast features Scott Weinger, Jonathan Freeman, Robin Williams, Linda Larkin, Frank Welker, Gilbert Gottfried, and Douglas Seale.

Lyricist Howard Ashman first pitched the idea, and the screenplay had to go through three drafts before Disney president Jeffrey Katzenberg greenlighted the production. The animators based their designs on the work of caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, and computers were used for both colouring and creating some animated elements. The musical score was written by Alan Menken and features six songs with lyrics written by both Ashman and Tim Rice, who took over after the former's death.

Aladdin was released on November 25, 1992 to positive reviews, despite some criticism from Arabs who considered the film racist, and was the most successful film of 1992, earning over $217 million in revenue in the United States, and over $504 million worldwide. The film also won many awards, most of them for its soundtrack. Aladdin's success led to many material inspired by the film such as two direct-to-video sequels, The Return of Jafar and Aladdin and the King of Thieves, an animated television series, toys, video games, spin-offs, and merchandise.

Contents |

Plot

Jafar, Grand Vizier to the Sultan of the fictional kingdom of Agrabah, is attempting to access the Cave of Wonders for a magical oil lamp containing a genie. After seeing a petty thief's failed attempt to enter the cave, he and his talking parrot, Iago, learn that only a "Diamond in the Rough" can enter the cave, or anyone accompanied by him.

Jasmine, the Sultan's daughter, frustrated with "having her life lived for her" and the obligation of marriage, escapes the palace and goes to Agrabah's marketplace. There she meets street rat Aladdin and his monkey, Abu. Jafar uses a machine to discover that Aladdin is the "diamond in the rough", and has him captured. Jasmine orders him released, but Jafar lies, telling her Aladdin had already been executed.

Jafar, disguised as an elderly man, releases Aladdin from prison and leads him to the Cave of Wonders. The tiger-shaped head of the cave tells them to touch nothing but the lamp. Aladdin enters the cave and encounters a magic carpet who guides him to the lamp. Abu tries to steal a ruby, which brings upon them the wrath of the Cave of Wonders, but the carpet helps them to the entrance. Jafar tries to kill Aladdin after getting the lamp, but Abu bites Jafar and takes the lamp back. Abu, the carpet and Aladdin fall back into the cave just as it closes. Jafar beams at finally getting the lamp; however, he cries out in agony when he realizes he doesn't have it.

When Aladdin awakens, Abu reveals that he sneakily took the lamp from Jafar. While trying to read an inscription on the lamp, Aladdin rubs it, unleashing the Genie who reveals he will grant Aladdin three wishes. However, he reminds him that he can't kill, make someone fall in love, or bring back the dead. Aladdin dupes Genie into freeing them from the cave without using a wish. While contemplating his wishes, Aladdin asks for Genie's opinion. Genie admits he would wish for freedom, since he is a prisoner to his lamp. Aladdin promises to wish him free for his last wish. He later tells Genie about Jasmine, and knows that the only way to be noticed by her if he was a prince. For his first wish, Aladdin asks to become a prince so he can marry Jasmine.

Jafar laments his failure to get the lamp but, thanks to Iago, later decides to trick the Sultan into arranging a marriage between himself and Jasmine, and then kill both the princess and her father. His plans are interrupted when Aladdin parades into the Sultan's palace as "Prince Ali". Jasmine rejects Ali, considering him a buffoon like all the other suitors before him. That night, Genie tells Aladdin to tell the princess who he really is, but Aladdin decides to remain the suave prince. He meets Jasmine, and after some convincing, takes her around the world on the magic carpet. During a fireworks show in China, Jasmine recognized Ali as the boy from the marketplace. Being demanded the truth, Aladdin instead fabricates a story that he sometimes dresses as a commoner to escape palace life. Aladdin returns her home and they kiss.

After parting with Jasmine, Aladdin is captured by Jafar and thrown into the ocean. But the Genie rescues Aladdin as his second wish. Aladdin returns to the palace, revealing Jafar's plot to Jasmine and the Sultan. Jafar, however, notices the lamp in Aladdin's possession, realizes Aladdin's identity, and escapes from the Sultan's bodyguards. Surprised by Aladdin's bravery, the Sultan decides Aladdin should be his successor. Aladdin faces a moral dilemma. Jasmine had fell in love with Ali, not Aladdin, and if she would ever find out at this point, he would lose her. Much to Genie's chagrin, Aladdin decides he has to wait before wishing Genie free, driving a wedge between the two. Iago, on Jafar's orders, steals Genie's lamp and brings it to Jafar, who becomes Genie's new master and uses his first wish to become sultan. When Jasmine and the Sultan refuse to bow to him, Jafar uses his second wish to become the most powerful sorcerer in the world, using his new powers not only force them to bow, but to also expose Aladdin and then send him and his friends to a far-off place.

Aladdin uses the magic carpet to return to Agrabah, where Jafar has imprisoned both Jasmine and the Sultan as his slaves. Jasmine distracts Jafar as Aladdin attempts to steal back the lamp, but the Jafar notices and attacks him. Jafar boasts that he is "the most powerful being on Earth", which causes Aladdin to shout out that Genie is more powerful. Faced with this realization, Jafar uses his final wish to become an 'all-powerful genie,' but is then surprised when Aladdin reminds him that genies are not free entities as he is sucked into his new black lamp, dragging Iago with him. Genie flicks the lamp across the desert.

Despite everything that happened, Jasmine understood Aladdin playing the prince because of the law. Genie suggests to him that the last wish can make him a prince again. Realizing that he cannot be someone he is not, Aladdin decides to keep his promise and wishe for Genie's freedom, much to Genie's surprise and happiness. Seeing Jasmine's love for Aladdin, the Sultan changes the law to allow her to marry whomever she chooses. Genie leaves to explore the world while Aladdin and Jasmine celebrate their engagement.

Cast and characters

- Scott Weinger as Aladdin / Prince Ali Ababwa: A poor but kind-hearted Agrabah thief. Brad Kane supplies the character's singing voice. Weinger sent in a homemade audition tape with his mother playing the Genie,[1] and after several call backs he found six months later that he had the part.[2]

- Robin Williams as The Genie/The Narrator: A comedic genie, with nigh omnipotent power that can only be exercised when his master wishes it. Clements and Musker wrote the part of the Genie for Williams, and when met with resistance created a reel of Williams' standup to animation of the Genie. When Williams watched the video, he "laughed his ass off" and agreed to do the project.[3]

- Jonathan Freeman as Jafar: The power-hungry Grand Vizier of Agrabah and the main antagonist of the film. Jafar was originally envisioned as an irritable character, but the directors decided that a calm villain would be scarier.[4] Animator Andreas Deja tried to incorporate Freeman's facial expressions into the character.[5]

- Linda Larkin as Princess Jasmine: The princess of Agrabah, who is tired of life in the royal palace. Lea Salonga supplies the character's singing voice. Larkin was chosen nine months after her audition, and had to adjust her pitch to reach the voice the filmmakers were looking for the character.[4]

- Frank Welker as Abu: Aladdin's kleptomaniac pet monkey with a high-pitched voice. The animators filmed monkeys at the San Francisco Zoo to study the movements Abu would have.[4] In the three years it took to record the film, Welker did not meet Weinger or Williams.[6] Welker also voiced Jasmine's tiger Rajah, and the Cave of Wonders.[7]

- Gilbert Gottfried as Iago: Jafar's sarcastic, foul-mouthed pet parrot sidekick. Iago's animator Will Finn tried to incorporate some aspects of Gottfried's appearance into Iago's design, specially his semi-closed eyes and the always-appearing teeth.[4]

- Douglas Seale as The Sultan: The pompous but kind ruler of Agrabah, who desperately tries to find a suitor for his daughter Jasmine. Some aspects of the character were inspired in the Wizard of Oz, to create a bumbling authority figure.[4]

- Jim Cummings as Razoul: The Captain of the Guard. He was named after layout supervisor Rasoul Azadani.[4]

- The Magic Carpet is a sentient carpet who is able to fly. Animator Randy Cartwright described working on the Carpet as challenging, since it is just a square shape, who expresses himself through pantomime — "It's sort of like acting by origami".[8] Cartwright kept folding a piece of cloth while animating to see how to position the Carpet.[8] After the character animation was done, the carpet's surface design was applied digitally.[5]

Production

Script and development

In 1988, lyricist Howard Ashman pitched to Disney the idea of an animated musical adaptation of Aladdin. After Ashman wrote some songs with partner Alan Menken and a film treatment,[9] a screenplay was written by Linda Woolverton, who had worked on Beauty and the Beast.[10] Then directors John Musker and Ron Clements joined the production, picking Aladdin out of three projects offered, which also included an adaptation of Swan Lake and King of the Jungle - that eventually became The Lion King.[11] Musker and Clements wrote a draft of the screenplay, and delivered it to studio chief Jeffrey Katzenberg in 1991. Katzenberg thought the script "didn't engage", and only approved it after the screenwriting duo Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio rewrote it.[9] Among the changes, the character of Aladdin's mother was removed, Princess Jasmine was made into a stronger character, Aladdin's personality was rewritten to be "a little rougher, like a young Harrison Ford,"[9][12] and the parrot Iago, originally conceived as a "British" calm and serious character, was reworked into a comic role after the filmmakers saw Gilbert Gottfried in Beverly Hills Cop II. Gottfried was cast to provide Iago's voice.[13] Several characters and plot elements are also based on the 1940 version of The Thief of Bagdad,[14][15] and many aspects of the traditional story were changed for the film — for instance, the setting is changed from "China" to a fictional Arabian city, Agrabah.[16] Elements from the story Ma'aruf the Cobbler and his Wife Fatimah, another story from One Thousand and One Nights, were also added in, with the final result being a blend of the original two stories.[17]

Design and animation

One of the first issues that the animators faced during production of Aladdin was the depiction of Aladdin himself.[19] Director and producer John Musker explains:

| “ | In early screenings, we played with him being a little bit younger, and he had a mother in the story. [...] In design he became more athletic-looking, more filled out, more of a young leading man, more of a teen-hunk version than before.[19] | ” |

He was initially going to be as young as 13, but that eventually changed to eighteen.[19] Aladdin was designed by a team led by supervising animator Glen Keane, and was originally made to resemble actor Michael J. Fox. During production, it was decided that the design was too boyish and wasn't "appealing enough," so the character was redesigned to add elements derived from actor Tom Cruise and Calvin Klein models.[3]

The design for most characters was based on the work of caricaturist Al Hirschfeld,[5] which production designer Richard Vander Wende also considered appropriate to the theme, due to similarities to the swooping lines of Persian miniatures and Arabic calligraphy.[8] Jafar's design was not based on Hirschfeld's work because Jafar's supervising animator, Andreas Deja, wanted the character to be contrasting.[20] Each character was animated alone, with the animators consulting each other to make scenes with interrelating characters. Since Aladdin's animator Glen Keane was working in the California branch of Walt Disney Feature Animation, and Jasmine's animator Mark Henn was in the Florida one at Disney-MGM Studios, they had to frequently phone, fax or send designs and discs to each other.[8]

For the scenery design, layout supervisor Rasoul Azadani took many pictures of his hometown of Isfahan, Iran for guidance.[4] Other inspirations for design were Disney's animated films from the 1940s and 50s and the 1940 film The Thief of Bagdad.[8] The coloring was done with the computerized CAPS process, and the color motifs were chosen according to the personality - the protagonists use light colors such as blue, the antagonists darker ones such as red and black, and Agrabah and its palace use the neutral color yellow.[4][5] Computer animation was used for some elements of the film, such as the tiger entrance of the Cave of Wonders and the scene where Aladdin tries to escape the collapsing cave.[5]

Musker and Clements created the Genie with Robin Williams in mind; even though Katzenberg suggested actors such as John Candy, Steve Martin, and Eddie Murphy, Williams was approached and eventually accepted the role. Williams came for voice recording sessions during breaks in the shooting of two other films he was starring in at the time, Hook and Toys. Unusually for an animated film, much of Williams' dialogue was ad-libbed: for some scenes, Williams was given topics and dialogue suggestions, but allowed to improvise his lines.[5] It was estimated that Williams improvised 52 characters.[21] Eric Goldberg, the supervising animator for the Genie, then reviewed Williams' recorded dialogue and selected the best gags and lines that his crew would create character animation to match.[5]

The producers added many in-jokes and references to Disney’s previous works in the film, such as a "cameo appearance" from directors Clements and Musker and drawing some characters based on Disney workers.[7] Beast, Sebastian from The Little Mermaid, and Pinocchio make brief appearances,[4] and the wardrobe of the Genie at the end of the film—Goofy hat, Hawaiian shirt, and sandals—are a reference to a short film that Robin Williams did for the Disney/MGM Studios tour in the late 80s.[7]

Robin Williams' conflicts with the studio

In gratitude for his success with the Disney/Touchstone film Good Morning, Vietnam, Robin Williams voiced the Genie for SAG scale pay ($75,000), on condition that his name or image not be used for marketing, and his (supporting) character not take more than 25% of space on advertising artwork, since Toys was scheduled for release one month after Aladdin's debut. For financial reasons, the studio went back on the deal on both counts, especially in poster art by having the Genie in 25% of the image, but having other major and supporting characters portrayed considerably smaller. The Disney Hyperion book Aladdin: The Making Of An Animated Film, listed both of Williams' characters "The Peddler" and "The Genie" ahead of main characters, but was forced to refer to him only as "the actor signed to play the Genie".[3]

Williams and Disney had a bitter falling-out, and as a result, Dan Castellaneta voiced the Genie in The Return of Jafar, the Aladdin animated television series, and had recorded his voice for Aladdin and the King of Thieves. When Jeffrey Katzenberg was fired from Disney and replaced by former 20th Century Fox production head Joe Roth (whose last act for Fox was greenlighting Williams' film Mrs. Doubtfire), Roth arranged for a public apology to Williams by Disney. Williams agreed to perform in Hollywood Pictures' Jack, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, and even agreed to voice the Genie again for the King Of Thieves sequel (for considerably more than scale), replacing all of Castellaneta's dialogue.[22]

Music

Composer Alan Menken and songwriters Howard Ashman and Tim Rice were praised for creating a soundtrack that is "consistently good, rivaling the best of Disney's other animated musicals from the '90s."[23] Menken and Ashman began work on the film together, with Rice taking over as lyricist after Ashman died of AIDS-related complications in early 1991.[24] Although fourteen songs were written for Aladdin, only six are featured in the movie, three by each lyricist.[25] The DVD Special Edition released in 2004 includes four songs in early animations tests, and a music video of one, "Proud of Your Boy", performed by Clay Aiken,[26] which also appears on the album DisneyMania 3.[27]

Themes

"The original story was sort of a winning the lottery kind of thing. When we got into it, particularly coming in at the end of 1980s, it seemed like an Eighties 'greed is good' movie. (...) Like having anything you could wish for would be the greatest thing in the world and having it taken away from you is bad, but having it back is great. We didn't really want that to be the message of the movie"

The filmmakers thought the moral message of the original tale was not appropriate, and decided to "put a spin on it", by making the fulfillment of wishes seem like a great thing, but eventually becoming a problem.[8] Another major theme was not trying to be what the person is not - both Aladdin and Jasmine get into trouble faking to be different people,[4] and the Prince Ali persona fails to impress Jasmine, who only falls for Aladdin when she finds out who he truly is.[28] It is also discussed on being "imprisoned", a fate that occurs to most characters - Aladdin and Jasmine are stuck to their lifestyles, Genie is attached to his lamp and Jafar, to the Sultan - and is represented visually by the prison-like walls and bars of the Agrabah palace, and the scene involving caged birds which Jasmine later frees.[4] Jasmine is also depicted as a different Disney Princess, being rebellious to the royal life and the social structure,[29] and trying to make her own way, unlike the princesses who just wait for rescue.[8]

Release and reception

Theatrical run

A large promotion campaign preceded Aladdin's debut in theaters, with the film's trailer being attached to most Disney VHS releases, and numerous tie-ins and licensees being released.[30] After a limited release on November 13, 1992,[31] Aladdin debuted on 1,131 theaters in November 25, 1992, grossing $19.2 million in its opening weekend — number two at the box office, behind Home Alone 2: Lost In New York.[32] It took eight weeks for the film to reach number one at the US box office, breaking the record for the week between Christmas and New Year's Eve with $32.2 million.[33] The film held the top spot five times during its 22-week run.[34] Aladdin was the most successful film of 1992 grossing $217 million in the United States and over $504 million worldwide.[35] It was the biggest gross for an animated film until The Lion King two years later.[36] As of 2010, it is the eighteenth highest grossing animated film and the third highest grossing traditionally animated feature worldwide, behind The Lion King and The Simpsons Movie.[37]

Critical response

Aladdin was well received by critics. The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 92% of critics gave the film a positive review based on a sample of 49 reviews, with an average score of 7.9/10.[38] Among the "Top Critics", it has a 100% positive review rating from eight critics.[39]

Most critics' praise went to Robin Williams' performance as Genie,[38] with Janet Maslin of The New York Times declaring that children "needn't know precisely what Mr. Williams is evoking to understand how funny he is".[40] Warner Bros. animator Chuck Jones even called the film "the funniest feature ever made."[9] James Berardinelli gave it 3.5 out of 4 stars, praising the "crisp visuals and wonderful song-and-dance numbers".[41] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone said the comedy made the film accessible to both children and adults,[42] a vision shared with Desson Howe of The Washington Post, who also said "kids are still going to be entranced by the magic and adventure."[43] Brian Lowry of Variety praised the cast of characters, describing the expressive magic carpet as "its most remarkable accomplishment" and considered that "Aladdin overcomes most story flaws thanks to sheer technical virtuosity".[44]

Some aspects of the film were widely criticized. Ed Gonzalez of Slant Magazine wrote a negative review, describing the film as racist, ridiculous, and a "narcissistic circus act" for Robin Williams.[45] IGN's review considered that besides the Genie and the cave-in scene, Aladdin was "totally by the numbers (...). You know how it will all turn out, it contains no surprises, and for that matter, very little that's truly special," and described the cast, particularly the protagonists, as "cookie-cutter characters".[26] Roger Ebert considered the music inferior to its predecessors The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, and claimed Aladdin and Jasmine were "pale and routine".[46]

Awards

Aladdin also received many award nominations, mostly for its music. It won two Academy Awards, Best Music, Original Score and Best Music, Original Song for "A Whole New World" and receiving nominations for Best Song ("Friend Like Me"), Best Sound Editing, and Best Sound.[47] At the Golden Globes, Aladdin won Best Original Song ("A Whole New World") and Best Original Score, as well as a Special Achievement Award for Robin Williams, with a nomination for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.[48] Other awards included the Annie Award for Best Animated Feature,[49] a MTV Movie Award for Best Comedic Performance to Robin Williams,[50] Saturn Awards for Best Fantasy Film, Performance by a Younger Actor to Scott Weinger and Supporting Actor to Robin Williams,[51] the Best Animated Feature by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association,[52] and four Grammy Awards, Best Soundtrack Album, and Song of the Year, Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal and Best Song Written for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media for "A Whole New World".[53]

Home media

The film was first released in VHS in October 1, 1993, as part of the "Walt Disney Classics" line. In its first week of availability, Aladdin sold over 10.8 million copies[54] and went on to sell over 25 million in total (a record only broken by the later release of The Lion King).[55] It entered moratorium on April 30, 1994.[56]

On October 5, 2004, Aladdin was released on DVD, as part of Disney's Platinum Edition line. The DVD release featured retouched and cleaned-up animation, prepared for Aladdin's planned but ultimately cancelled IMAX reissue in 2003,[57] and a second disc with bonus features. Accompanied by a $19 million marketing campaign,[58] the DVD sold about 3 million units, less than any of the other Platinum Edition titles so far.[59] The film's soundtrack was available in its original Dolby 5.1 track or in a new Disney Enhanced Home Theater Mix.[26] The DVD went into moratorium on January 2008, along with its sequels.[60]

Controversies

One of the verses of the opening song "Arabian Nights" was altered following protests from the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC). The lyrics were changed in July 1993 from "Where they cut off your ear if they don't like your face/It's barbaric, but, hey, it's home," in the original release to "Where it's flat and immense and the heat is intense/It's barbaric, but, hey, it's home." The change first appeared on the 1993 video release.[61] The original lyric was intact on the initial CD soundtrack release, but the re-release uses the edited lyric. The rerecording has the original voice on all other lines and then a noticeably deeper voice says the edited line. Entertainment Weekly ranked Aladdin in a list of the most controversial films in history, due to this incident.[62] The ADC also complained about the portrayal of the lead characters Aladdin and Jasmine. They criticized the characters' Anglicized features and Anglo-American accents, in contrast to the other characters in the film, which are dark-skinned, have Arab accents and grotesque facial features, and appear villainous or greedy.[61]

Protests were also raised to another scene. When Aladdin is attacked by the tiger Rajah on the palace balcony, Aladdin quietly says "Come on... good kitty, take off and go..." and the word "kitty" is overlapped by another, unidentifiable sound, possibly Rajah's snarl. Some people reported hearing "Good teenagers, take off your clothes,"[63] which they considered a subliminal reference to promiscuity. Because of the controversy, Disney replaced the phrase with "Down, kitty" on the DVD release.[64]

Animation enthusiasts have noticed similarities between Aladdin and Richard Williams's unfinished film The Thief and the Cobbler (also known as Arabian Knight under Miramax Films and The Princess and the Cobbler under Majestic Films International). These similarities include a similar plot, similar characters, scenes and background designs, and the antagonist Zig-Zag's resemblance in character design and mannerisms to Genie and Jafar.[65][66] Though Aladdin was released prior to The Thief and the Cobbler, The Thief and the Cobbler was started much earlier in the 1960s, its production being mired in difficulties including financial problems, copyright issues, and late production times caused by separate studios trying to finish the film after Richard Williams was fired from the project for lack of finished work.[67] The late release coupled with Miramax (a Disney-owned studio) purchasing and re-editing the film, has sometimes resulted in The Thief and the Cobbler being labeled a copy of Aladdin.[66]

Legacy

Sequels and spin-offs

Aladdin was followed by Disney's first direct-to-video sequel, The Return of Jafar in 1994. The film saw the debut of a new character, Abis Mal, voiced by Jason Alexander, and all of the original cast, except for Robin Williams, replaced by Dan Castellaneta, and Douglas Seale, replaced by Val Bettin. The plot mainly focused on Jafar seeking revenge on Aladdin. However, this time, with Iago on Aladdin's side, Abis Mal becomes Jafar's new henchman.[68] Shortly after The Return of Jafar, the Aladdin TV Series was aired on television. The episodes focused on Aladdin's adventures after the events of the second film.[69] In 1996, the final sequel to Aladdin, Aladdin and the King of Thieves was released on video. The story concludes as Aladdin and Jasmine are about to be married and Aladdin discovers that his father is still alive, but is the king of all thieves in Agrabah.[68]

The Aladdin characters later made a crossover with Hercules: The Animated Series,[70] and were featured as guests in the television series House of Mouse and related works to those series—Jafar was the leader of the villains in Mickey's House of Villains.[71]

The film also inspired a Disney On Ice presentation,[72] and two attractions in Disney's theme parks: "The Magic Carpets of Aladdin", a Dumbo the Flying Elephant-like ride at both Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World Resort and Walt Disney Studios Park at Disneyland Resort Paris;[73][74] and the show Disney's Aladdin: A Musical Spectacular at Disney's California Adventure Park.[75]

Video games

Along with the film release, three different video games based on Aladdin were released. A coproduction between Virgin Games and Walt Disney Feature Animation for the Sega Genesis was released in late 1993 and later ported to Nintendo Entertainment System, PC, Game Boy and Game Boy Color.[76] Another by Capcom for the Super Nintendo, ported to the Game Boy Advance in 2002.[77][78] Another by SIMS for the Sega Game Gear and Sega Master System.[79]

The television series inspired another game by Argonaut Games, entitled Aladdin: Nasira's Revenge and released in 2000 for the PlayStation and PC.[80] Also, in 2004 Vivendi Universal released Disney's Aladdin Chess Adventures, a chess computer game with the Aladdin license.[81]

The Kingdom Hearts series features a playable Aladdin world known as Agrabah.[82] In Kingdom Hearts and Kingdom Hearts: Chain of Memories, the plotline is loosely related to the storyline of the original film.[82][83] In Kingdom Hearts II, it is a mixture of Aladdin and The Return of Jafar.[84] Genie is also a recurring summon in the series.[82]

References

- ↑ Abbott, Jim (January 5, 1993). "As Genie, mom helped grant son's wish for 'Aladdin' role". St. Paul Pioneer Press. http://www.scottweinger.net/article13.html. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Caporaso, Jenna; Trucks, Leigh; Pompa, Andrew (February 27, 1994). "Aladdin's Voice Speaks". The Charlotte Observer. http://www.scottweinger.net/article15.html. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "DISNEY'S GOT A BRAND-NEW BAGHDAD". Entertainment Weekly. 1992-09-04. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,312562,00.html. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Pop Up Fun Facts. [DVD]. Aladdin Platinum Edition Disc 1: Walt Disney Home Video. 2004.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Diamond in the Rough: The Making of Aladdin. [DVD]. Aladdin Platinum Edition, Disc 2: Walt Disney Home Video. 2004.

- ↑ Kalidor (September 22, 2006). "The Allspark Interviews Legend Frank Welker". allspark.com. http://www.allspark.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1&Itemid=3. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ron Clements, John Musker, Amy Pell.Aladdin audio commentary - The Filmmaker's

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Culhane, John (1993-08-15). Disney’s Aladdin The Making Of An Animated Film. Disney Editions. ISBN 156282757X.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "Aladdin's Magic". TIME. 1992-11-09. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,976941-2,00.html. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "Aladdin: Crew Reunion". Animated Views. http://animatedviews.com/2005/aladdin-crew-reunion/. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ↑ "Show 009 - Ron and John, Part Three". The Animation Podcast. 2005-11-01. http://animationpodcast.com/ronandjohn-part-three/. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ↑ "Aladdin DVD review". UltimateDisney.com. http://www.ultimatedisney.com/aladdin.html. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ↑ John Musker, Ron Clements. (2004). Aladdin: Platinum Edition (Disc 2). [DVD]. Walt Disney Home Video.

- ↑ "Fantasy: The Thief of Bagdad". Foster On Film. http://www.fosteronfilm.com/fantasy/thiefbagdad.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ↑ Bernstein, Matthew; Studlar, Gaylyn (1997). Visions of the East. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1860643051. http://books.google.com/books?id=q2_E_gl9BbYC.

- ↑ Dr. Ali Behdad. (2004). Aladdin: Platinum Edition (Disc 2). [DVD]. Walt Disney Home Video.

- ↑ http://www.wollamshram.ca/1001/Vol_10/tale169.htm

- ↑ John Musker, Ron Clements. (2004). "Art Review". [DVD]. Aladdin: Platinum Edition (Disc 2): Walt Disney Home Video.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Thomas, Bob: "Chapter 9: A New Tradition", pages 133-135. Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Hercules, 1997

- ↑ "Aladdin animator used subtlety to design strong villain". The Tech. 1992-11-20. http://tech.mit.edu/V112/N64/aladdin.64a.html.

- ↑ James Lipton (host). (2001). Inside the Actors Studio: Robin Williams. [Documentary]. Bravo.

- ↑ Hill, Jim (April 2000). "Be Careful What You Wish For". Jim Hill Media. http://jimhillmedia.com/blogs/jim_hill/archive/2000/12/31/312.aspx. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ↑ Phares, Heather. "Aladdin soundtrack review". Allmusic. http://www.allmusic.com/album/r110157. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ Alan Menken: Musical Renaissance Man. [DVD]. Aladdin Platinum Edition, Disc 2: Walt Disney Home Video. 2004.

- ↑ Daly, Steve (1992-12-04). "Unsettled score". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,312563,00.html. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "Aladdin: Ultimate DVD review". IGN. 2004-09-17. http://dvd.ign.com/articles/549/549036p1.html. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "DisneyMania 3". Disney. http://disneymusic.disney.go.com/albums/disneymania3.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ Smith, Dave (1996-08-15). Disney A to Z: The Official Encyclopedia. Disney Editions. ISBN 0-7868-6223-8.

- ↑ Marzolph, Ulrich (2006). The Arabian Nights reader. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814332595. http://books.google.com.br/books?id=AKd6mZSGsVUC&pg=PA276&lpg=PA276.

- ↑ Daly, Steve; Ascher-Walsh, Rebecca (1993-03-12). "Arabian Sheikdown". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,305817,00.html. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ↑ "Weekend Box Office Results for November 13–15, 1992". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/weekend/chart/?yr=1992&wknd=46&p=.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Natale, Richard (1992-11-30). "Holiday B.O. gobbles up big bucks". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR101610.html?categoryid=13&cs=1. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Fox, David J. (1993-01-26). "'Aladdin' Finally Hits No. 1 and a Record in Sales Too". Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/1993-01-26/entertainment/ca-2081_1_weekend-box-office. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ "Aladdin (1992) - Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?page=weekend&id=aladdin.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ "Aladdin box office info". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=aladdin.htm. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ↑ "The Lion King (1994)". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=lionking.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ "The Simpsons Movie (2007)". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=simpsons.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Aladdin at Rottentomatoes.com". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1042582-aladdin/. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Aladdin: Cream of the Crop". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1042582-aladdin/?critic=creamcrop. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (1992-11-11). "Disney Puts Its Magic Touch on 'Aladdin'". The New York Times. http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9E0CE7DC1138F932A25752C1A964958260. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Berardinelli, James (1992). "Aladdin". Reelviews. http://www.reelviews.net/php_review_template.php?identifier=41. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Travers, Peter (November 1992). "Aladdin". Rolling Stone (644). Archived from the original on 2008-06-18. http://web.archive.org/web/20080618163432/http://www.rollingstone.com/reviews/movie/5947957/review/5947958/aladdin. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Howe, Desson (1992-11-27). "‘Aladdin’". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/aladdinghowe_a0af3c.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Lowry, Brian (1992-11-04). "Aladdin". Variety. http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117900071.html?categoryid=31&cs=1. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Gonzalez, Ed (2004-09-24). "Aladdin". Slant Magazine. http://www.slantmagazine.com/film/review/aladdin/1172. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (1992-11-25). "Aladdin review". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19921125/REVIEWS/211250301/1023. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ↑ "Awards and Nominations for Aladdin". AMPAS. http://awardsdatabase.oscars.org/ampas_awards/DisplayMain.jsp?curTime=1274335509275. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "SEARCH — Aladdin". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. http://www.goldenglobes.org/browse/film/23558. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "Legacy: 21st Annual Annie Award Nominees and Winners (1993)". Annie Awards. http://annieawards.org/21stwinners.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ "1993 MTV Movie Awards". MTV. http://www.mtv.com/ontv/movieawards/1993/. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "Past Saturn Award Winners". Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films. http://www.saturnawards.org/past.html. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ↑ "18TH Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". LAFCA. http://www.lafca.net/years/1992.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ Pareles, Jon (1994-03-02). "Top Grammy to Houston; 5 for 'Aladdin'". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1994/03/02/movies/top-grammy-to-houston-5-for-aladdin.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ "Arabian Might". Entertainment Weekly. 1993-10-15. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,308423,00.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ "Disney Rubs Aladdin's Lamp". Movie Web. http://www.movieweb.com/news/NEkGOqpnt2XAok. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ↑ Nichols, Peter M. (1994-05-20). "Home Video". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1994/05/20/arts/home-video-149802.html. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ↑ Hill, Jim (2004-10-12). ""Aladdin" Platinum Edition sets the gold standard for Disney DVD". http://jimhillmedia.com/blogs/jim_hill/archive/2004/10/11/478.aspx. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

- ↑ Arnold, Thomas K. (2005-08-09). "Best sellers". The Hollywood Reporter. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/hr/search/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1001011344. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ McCourt, Judith (2004-12-02). "DVD Player Penetration Drives October Sales Growth". http://www.homemediamagazine.com/news/dvd-player-penetration-drives-october-sales-growth-6917. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ↑ "Out of Print Disney DVDs". UltimateDisney.com. http://www.ultimatedisney.com/OOP.htm. Retrieved 24 September 2006.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "Arab Stereotypes and American Educators". American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. http://www.adc.org/index.php?id=283. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "The 25 Most Controversial Movies Ever". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,1202224,00.html. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "How a Rumor Spread About Subliminal Sex In Disney's 'Aladdin'". The Wall Street Journal. 1995-10-25. http://www.snopes.com/disney/info/aladwsj.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ "Disney (Take Off Your Clothes!)". Snopes. http://www.snopes.com/disney/films/aladdin.asp. Retrieved 2007-03-24.. The source compiles and cites four major newspaper references.

- ↑ "The Thief and the Cobbler review". DVD snapshot. http://www.dvdsnapshot.com/January07Review/ThiefAndCobbler.html.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 James, Caryn (1995-08-26). "The Thief and the Cobbler NY Times review". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1995/08/26/movies/film-review-a-late-finisher-about-old-araby.html.

- ↑ "The Best Animated Movie You've Never Heard Of". TV Guide. 2006-11-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20080113004732rn_1/community.tvguide.com/blog-entry/TVGuide-Editors-Blog/Ask-Flickchick/Best-Animated-Movie/700013169. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Aladdin II & III Collection DVD Review". Ultimate Disney. http://www.ultimatedisney.com/aladdinsequels.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ "Screen Test". Entertainment Weekly. 1994-11-25. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,304602,00.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ "Hercules and the Arabian Night". Hercules: The Animated Series. ABC. 1998–1999. Transcript.

- ↑ "Mickey's House of Villains DVD Review". Ultimate Disney. http://www.ultimatedisney.com/houseofvillains.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ Deknock, Jan (1998-03-06). "`Aladdin' Takes Fans On An Icy `Magic-Carpet Ride'". The Seattle Times. http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19980306&slug=2738043. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "The Magic Carpets of Aladdin". Walt Disney World. http://disneyworld.disney.go.com/parks/magic-kingdom/attractions/magic-carpets-of-aladdin/. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ "Les Tapis Volants — Toon Studio — Disneyland Resort Paris". Disneyland Resort Paris. Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. http://web.archive.org/web/20080822130155/http://parks.disneylandparis.co.uk/walt-disney-studios-park/lots/toon-studio/attractions/les-tapis-volants.xhtml. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ "Disney's Aladdin — A Musical Spectacular". Disney's California Adventure Park. http://disneyland.disney.go.com/disneyland/en_US/parks/entertainment/detail?name=AladdinEntertainmentPage. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Disney's Aladdin for Genesis at MobyGames. Accessed October 6, 2010.

- ↑ Disney's Aladdin for SNES at MobyGames. Accessed October 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Disney's Aladdin Company Line". GameSpot. 2004-05-12. http://www.gamespot.com/gba/action/disneysaladdin/news.html?sid=6097907. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ Disney's Aladdin for Master System and Game Gear at MobyGames. Accessed October 6, 2010

- ↑ "Aladdin Nasira's Revenge gamespace". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/ps/action/aladdinnasirasrevenge/index.html. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "Disney's Aladdin Chess Adventures gamespace". IGN. http://pc.ign.com/objects/683/683949.html. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 Birlew, Dan (2003). Kingdom Hearts Official Strategy Guide. BradyGames. ISBN 0-7440-0198-6.

- ↑ Hollinger, Elizabeth (2004). Kingdom Hearts: Chain of Memories Official Strategy Guide. BradyGames Publishing. ISBN 0-7440-0473-X.

- ↑ Hollinger, Elizabeth (2006). Kingdom Hearts II Official Strategy Guide. BradyGames Publishing. ISBN 0-7440-0526-4.

External links

- Aladdin at the Internet Movie Database

- Aladdin at Allmovie

- Aladdin at Box Office Mojo

- Aladdin at Rotten Tomatoes

- Aladdin at the Big Cartoon DataBase

| Preceded by "Beauty and the Beast" from Beauty and the Beast |

Academy Award for Best Original Song "A Whole New World" 1992 |

Succeeded by "Streets of Philadelphia" from Philadelphia |

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||